ႏိုုင္ငံၾကီးးေတြ ႏိုုင္ငံေရးကစားကြက္ထဲ ေရာက္မွန္းမသိေရာက္လာရေသာ ဒုုကၡေရာက္ေနရတဲ့ ျမန္မာျပည္.....

ရုုိဟင္ဂ်ာျပသနာဆုုိတာ ျမန္မာ့ေျမက သဘာဝဓါတ္ေငြ႕နဲ႕ သယံဇာတေတြကုုိ တရုုတ္လက္ထဲ ေရာက္မွာ မလုုိလားလုုိ႕ အေမရိကန္ဖန္တည္း လုုိက္တဲ့ ပဋိပကၡျဖစ္ပါတယ္ တဲ့။

အဓ္ိက ေပါက္ေဖာ္ႀကီးရဲ ေရွးကပုုံျပင္ အိမ္မက္ ႕ ပိုးလမ္းမစီမံကိန္းကို ဖ်က္စီးျခင္တာဗ်!

ရုုိဟင္ဂ်ာျပသနာဆုုိတာ ျမန္မာ့ေျမက သဘာဝဓါတ္ေငြ႕နဲ႕ သယံဇာတေတြကုုိ တရုုတ္လက္ထဲ ေရာက္မွာ မလုုိလားလုုိ႕ အေမရိကန္ဖန္တည္း လုုိက္တဲ့ ပဋိပကၡျဖစ္ပါတယ္ တဲ့။

CRISIS IN MYANMAR

Oil, Gas, Geopolitics Guide US Hand In Playing The Rohingya Crisis

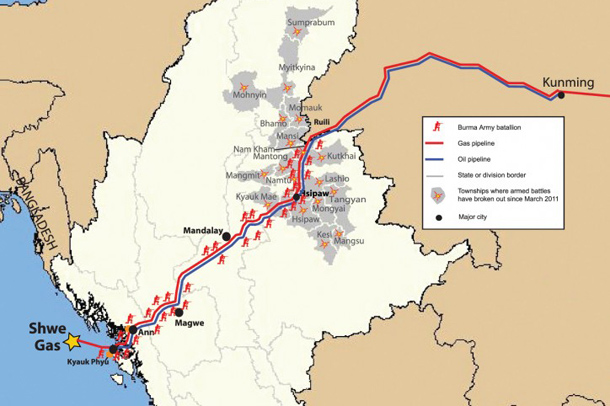

Internal conflict, appropriately located, spells geopolitical opportunity. With U.S. ally Saudi Arabia funding and stoking Rohingya insurgencies, the U.S. creates a chance to blockade China’s oil supply and provide Aung San Suu Kyi the military cooperation needed to wrest Myanmar back from Chinese influence.

ဒီပိုးလမ္းမတကယ္ုျဖစ္သြားရင္ေစ်းေပါတဲ့ ပိုလ်ံေနတ့ဲတ႐ုတ္ထုတ္ကုန္ေတြ အေနာက္ဖက္ကိုအလြယ္တကူ ေရာက္ကုန္ မွာဆိုးလို႔ပါ!

အခုုေတာင္ အေနာက္အုုပ္စုုေတြ တရုုတ္ႏွင့္ကုုန္သြယ္တာ ဘီလ ွ်ံေက်ာ္အရႈံးျပေနတာေလ?

Win-Win cooperation along the 'One Belt One Road'!

One Belt One Road' (OBOR) stands for the double initiatives proposed by The People's Republic of China in 2013, with the main aim of promoting intercontinental trade and building infrastructure to connect Europe, Asia and Africa through land and sea.

OBOR comprises the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’. The historic connotation is not accidental: the benefits of lively economic and cultural activity along the historic Silk Road should be revived, deepened and expanded with modern technology and know-how. So, this time, instead of depending on animals for transport, roads, ports and railways should be built to connect economies, countries, companies, international and regional organisations and people. Futuristic endeavors such as going from Berlin to Beijing in one day by a high velocity train should become a reality if China’s proposals will get willing partners.

The ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ focuses on linking China to Europe through Central Asia and Russia; China to the Middle East through Central Asia; and bringing together China and Southeast Asia and South Asia and the Indian Ocean. The ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ focuses on using Chinese coastal ports to link China with Europe through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean and connecting China with the southern Pacific Ocean through the South China Sea. The imagined routes cover more than 60 countries and regions, currently accounting for some 30 percent of global GDP and more than 35 percent of the world's merchandise trade.

At this year’s Munich Security Conference, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi expressed his satisfaction with the impact of the initiative over the last three years. In his words, the construction progress and results have gone beyond expectations. For example, as of March 2016, construction had begun on a railway between Hungary and Serbia, the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail, the China-Laos railway and the China-Thailand railway. These railways represent the first steps towards a Trans-Asia Railway Network and other expressway projects are under construction.

Also known as the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI), OBOR is more than just building railways and selling goods. As stated in the Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, published by the Chinese Development and Reform Commission in 2015:

“The initiative to jointly build the Belt and Road, embracing the trend towards a multi-polar world, economic globalisation, cultural diversity and greater IT application, is designed to uphold the global free trade regime and an open world economy in the spirit of open regional cooperation. It is aimed at promoting orderly and free flow of economic factors, highly efficient allocation of resources, and deep integration of markets; encouraging the countries along the Belt and Road to achieve economic policy coordination and carry out broader and more in-depth regional cooperation of higher standards; and jointly creating an open, inclusive and balanced regional economic cooperation architecture that benefits all. Jointly building the Belt and Road is in the interests of the world community”.

The document further stresses the need for upholding international law when seeking the ‘biggest common denominator’ for interests, strengths and potential of all parties, whether public or private. What is more, OBOR provides a “blueprint for global development in the new world order”. Recognition that the global economy is changing is strengthened in the face of recent isolationist and nationalistic predictions for the foreign economic policy of the USA, which suddenly sees the global economy as a zero-sum game. OBOR can serve as a reminder of the yet unfulfilled promises of economic globalisation to bring prosperity to all.

And China is prepared to put its money where its mouth is. Hundreds of billions of dollars are ready to be invested into five key areas of focus: policy coordination, infrastructure development, investment and trade facilitation, financial integration, and cultural and social exchange. The Silk Road Fund, the China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China and the two newly established multilateral development banks, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank of the BRICS, are all taking part in OBOR. To counter the initial skepticism provoked by the magnitude of the initiative in many countries, China is also willing to put in the needed diplomatic work to build trust, make its goals clearly heard and find appropriate partners and projects. As stressed many times, OBOR is not a one-sided, already delineated project, nor is it a program of Chinese international aid. It is an inclusive partnership building process which depends on dialogue and consultation with and joint contribution of all interested parties.

In the words of Foreign Minister Wang Yi: "OBOR is already actively supported by more than 100 countries and international organisations." On the other hand, it offers global businesses - from multinationals to small- and medium-sized enterprises - unparalleled opportunities to tap into new markets along the Belt and Road and gain deeper access to markets on the Chinese mainland, ASEAN, the Middle East, and Central and Eastern Europe. Projects are to be prepared until 2020, with implementation starting in 2021 and lasting until 2049.

One of the most important in the series of high-level events, summits, conferences and meetings that took place in several countries since making the OBOR initiative public will be held in May this year in Beijing. Hailed by the Foreign Minister Wang Yi as the Chinese diplomatic event of the year, the International Cooperation Summit Forum on the “Belt and Road” Initiative will focus on anti-protectionism, restating the potential of free trade and working with existing free trade regimes to bring tangible benefits to all involved regions, countries, communities and individuals more successfully.

Tags: OBOR, china, economic interdependence, Wang Yi

Ref:http://

ရုုိဟင္ဂ်ာျပသနာဆုုိတာ

ျမန္မာ့ေျမက သဘာဝဓါတ္ေငြ႕နဲ႕ သယံဇာတေတြကုုိ တရုုတ္လက္ထဲ ေရာက္မွာ

မလုုိလားလုုိ႕ အေမရိကန္ဖန္တည္း လုုိက္တဲ့ ပဋိပကၡျဖစ္ပါတယ္ တဲ့။

Oil, Gas and Geopolitics: US Hand in Playing the Rohingya Crisis against China (By Whitney Webb Global Research)

Internal conflict, appropriately located, spells geopolitical

opportunity. With U.S. ally Saudi Arabia funding and stoking Rohingya

insurgencies, the U.S. creates a chance to blockade China’s oil supply

and provide Aung San Suu Kyi the military cooperation needed to wrest

Myanmar back from Chinese influence.

In recent years, Myanmar

(formerly Burma) has only rarely been in the news. The quiet treatment

owed much to the assumption that the country’s fledgling democracy was

in “good hands” once the U.S-backed 1991 Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung

San Suu Kyi gained renewed political prominence after the 2015 elections

and assumed the office of state counselor a year later. However, the

tide of international public opinion has been turning sharply against

Suu Kyi as human rights activists, the United Nations and several other

Nobel laureates have strongly criticized her handling of what has now

become known as the “Rohingya crisis.”

The crisis centers on the

plight of the Rohingya, a historically persecuted Muslim minority living

in Myanmar’s coastal Rakhine state (formerly Arakan state). The

Rohingya are also stateless, as Myanmar’s government has long refused to

recognize their centuries-long claim to the region and has asserted on

several occasions that the Rohingya are not native to Myanmar but

instead “illegal immigrants” from neighboring Bangladesh. Deprived of

citizenship and thus of basic rights, their suffering has been

compounded by Myanmar’s government, which has used the military to

violently intimidate the Rohingya and force them from their lands.

This month, in particular, the corporate media — as well as several

prominent human rights organizations and international bodies, such as

the UN — have given unprecedented attention to the conflict. Last

Monday, for example, Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, the United Nations high

commissioner for human rights, accused Myanmar of undertaking “a

textbook example of ethnic cleansing” and stated that Myanmar’s campaign

against the Rohingya violated international law. In the first two weeks

of September, corporate media outlets have reported extensively on the

crisis. Just last week, CNN published 13 different articles about the

Rohingya’s plight. Calls have mounted for Suu Kyi, as Myanmar’s leader,

to intervene.

Given the recent flurry of press coverage and the

spike in concern among international bodies such as the United Nations,

one might assume that the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya by Myanmar’s

government is a recent phenomenon. However, in reality, the conflict

itself is nearly a century old and its current escalation did not begin

this year, but rather in 2011, and has continued to worsen ever since.

Furthermore, numerous other instances of genocide, such as the Saudis’

destruction of Yemen and Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Palestine, are

hardly touched by the corporate media or mentioned in mainstream

political discourse.

So why the sudden interest in Myanmar?

Oil and Gas Pipelines

Like so many other cases of ethnic cleansing, the Rohingya conflict is

essentially a conflict over resources, namely oil and gas. In 2004, a

massive natural gas field, named Shwe in honor of the long-time leader

of Myanmar’s military junta, was discovered off the coast of Myanmar in

the Bay of Bengal. In 2008, the China National Petroleum Corporation

(CNPC) secured the rights to the natural gas and bestowed upon the field

its honorific name. Construction began a year later on two 1,200 km

overland pipelines that would cross from Myanmar’s Rakhine state – home

of the Rohingya – to the Yunnan province of China.

The pipelines —

one carrying gas and the other carrying oil from the Middle East and

Africa, brought to Myanmar by ship — missed their targeted dates for

completion. The gas pipeline became operational in 2014 and carries more

than 12 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year to China. The oil

pipeline has proven more difficult to construct and is set to be

completed later this year. Once completed, it will allow China easier

access to oil from the Middle East and Africa and will reduce the

transport time of such oil by as much as 30 percent.

Ref:Thet Thet Tun FB

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment